South Baldy Snow Camp, 2016

An igloo in New Mexico

I have spent an unhealthy amount of my life in Socorro, New Mexico. While it is a great place for some people, it is not right for me. For example, there just aren't many opportunities to build an igloo. Sure, in northern New Mexico you often get enough snow. Thus the skiing in Taos and Santa Fe. But you don't get that type of snow in Socorro.

Naturally I was not in the area for the January 2016 snowstorm; good snowstorms always pick the week that I am out of town. When I got back there was just enough good wind blown snow on top of South Baldy. Obliviously I had to build an igloo and spend the weekend in it.

One of the challenges of snow camping is accessing the good snow. The roads and trails are snowed in, and finding parking is hard. New Mexico Tech had plowed the road up South Baldy, making access much easier. Tire chains were still highly advisable, lest you hit an icy patch and slide off the mountainside.

I went up the weekend before and built a snow house. That way I have some shelter up for the following weekend, and can check the snow condition. I started by quarrying some snow blocks.

In the unlikely event that the reader hasn't quarried their own snow blocks and built a snow house, here is the short version of how it works. You find a nice, wind-blown snow drift. Dig a hole 3 or more feet deep, looking for wind-packed snow with the consistency of styrofoam. Square off one side of the hole. Use a regular hand saw to start cutting out snow blocks.

To make a snow house, make a trench by quarrying the blocks in one direction. Then roof over the trench by leaning the snow blocks against each other.

I wondered if the nearby Magdalena Ridge Observatory noticed my work. If they did, they didn't give any sign of it.

If you can make a trench and cut snow blocks, the snow house is one of the best options for a snow shelter, especially in bad situations. It insulates well, protects from blizzards, and is a lot faster, and a lot less work, than making a snow cave or igloo. You can also make it in worse snow conditions.

Once you have the roof up you can dig the floor down and sides out as time allows. You also need to plug most of the holes in the roof, but leave some for breathing. If a blizzard comes through and dumps a few feet of snow you have to keep your air hole open as suffocation is a concern.

Having built the snow house, I headed back to town for the week.

The view down Sawmill Canyon was nice. It is rare to see this much snow in central New Mexico

I returned the following weekend with gear to spend the night. A lot of melting occurred, but at least the snow house was intact. Even in January, weather in the land of adobe just isn't good for snow shelters.

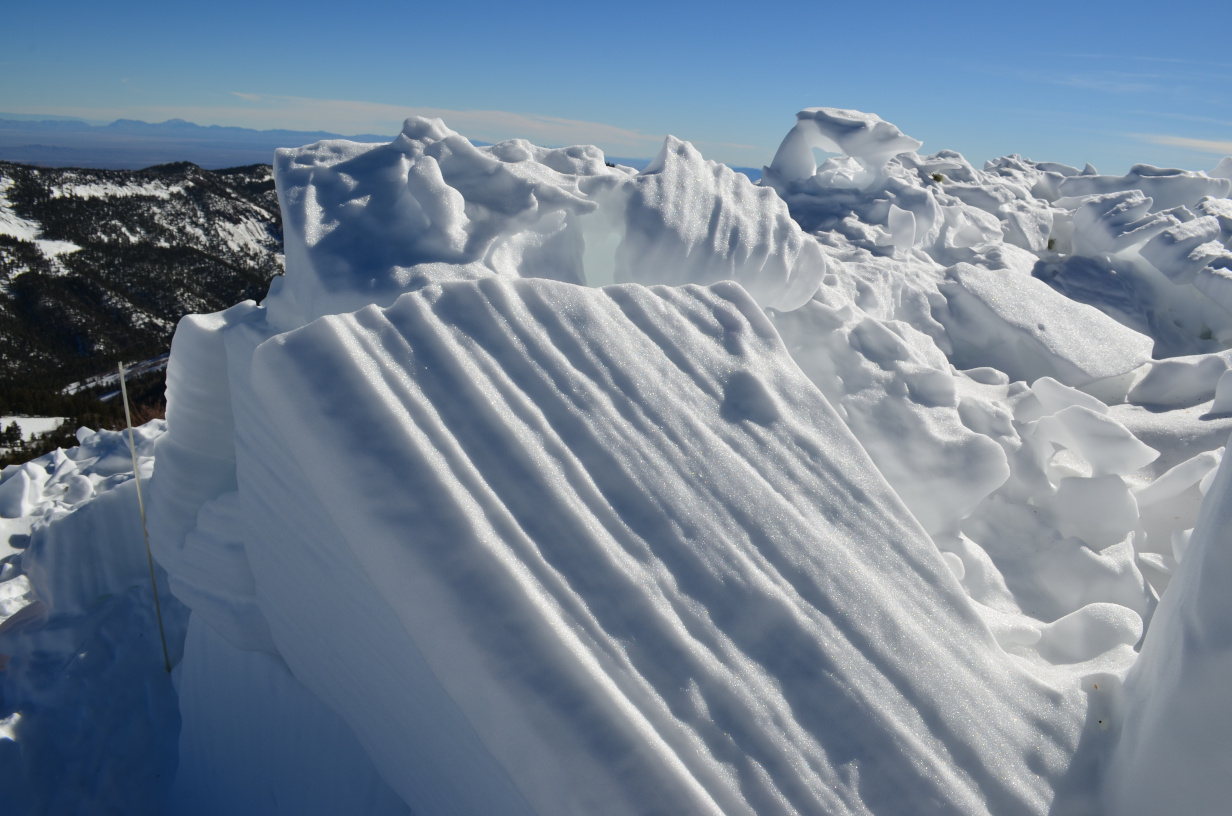

The melting revealed a neat layered pattern in the snow block. No, you can't count the layers in a snow block to tell how old it is.

The first step in building the igloo was to draw a circle where I wanted it to go. I placed it a short distance from one end of the snow house so I could connect the two later on.

Having turned my old quarry into a snow house, I had to start a new one. An igloo takes a lot of snow blocks, so think about where you want the quarry, and resulting pit, to be.

The first blocks are laid...

The trick to doming over an igloo is to spiral it. When a snow block is leaning over you can, most of the time, get it to stay put if 3 corners are held in place. The trick is having a spiral so that one row of blocks climbs on top of another. Once above ground level, every block then has 3 corners held when you place it.

By night time I was ready to move into the igloo. I hung a gas-powered lantern near a vent in the roof.

The (now connected) snow house served as a bed room and the igloo as a kitchen and living room. The camp stove had an alcove with its own vent. Note: propane stoves tend to freeze up if used for winter camping. Liquid fuel stoves tend to be better.

One trick to keeping the igloo warm: have the lowest point on the entry tunnel roof below the floor of the igloo. Warm air then pools in the igloo.

The igloo at night with the Rio Grande Valley and part of Socorro in the background.

Magdalena Ridge at night.

The road to Langmuir is littered with old military equipment...

The scientists running Langmuir Laboratory have done a very good job of keeping their costs down. A lot of the equipment was military surplus or other salvage. They use it until it is dead and then use it some more. Quite the opposite of the shiny high-dollar labs that are so common.

Langmuir Laboratory for Atmospheric Research is primarily a lightning research laboratory, for which the site is ideal.

An alternate theory is that they set out to experimentally determine if 70's sci-fi style mad scientists were possible. They set up a fortress-style lab on top of a mountain with assorted catwalks and platforms. And a rotating turret, a radar, a weather balloon launching facility, welded-steel underground bunkers, backup generators, plenty of military surplus hardware, and lots of mysterious scientific equipment. They had a couple mile long cable between two peaks for cloud electrification experiments. And the scientists started launching rockets to trigger lightning strikes.

But their efforts failed to produce a single mad scientist. Instead of trying to take over the world, their scientists started writing grant proposals. And teaching science classes. And publishing useful world-class research on lightning. So NMT's attempt to make a mad scientist failed. Instead they discovered the sad truth: most "mad scientists" are actually just mad engineers.

On a more serious note, Langmuir Laboratory deserves substantial credit for advancing our understanding of lightning, leading to dramatic improvements in lightning safety.

Toward the end of the day, I had a couple visitors. They enjoyed the igloo.

And, having visitors, we also have a rare picture of the author of this website!

A good trip. The Igloo didn't last long; it was melted out in under a week. There really wasn't much snow by my standards. But it was nice to build another igloo, especially in New Mexico.

Last Updated: July 2019; Original Posting.

© David C. Hunter, 2016-2019

fb {at) dragonsdawn (dot] org